“Interdependency is key to God’s self revelation and our own relationship with one another.”

–Rev. Dr. Michael Battle

In a recent conversation with our Mosaic peacemakers cohort on Ubuntu theology, the Very Rev. Dr. Michael Battle invited our community into an entirely different way of seeing the world and ourselves in it—one rooted in God’s self-revelation.

“The doctrine of God is very much the same as Ubuntu. Our understanding of Ubuntu culturally as well as spiritually can help us in our ministries.”

Ubuntu’s foundation, Rev. Battle explained, is found in Jesus’ petitionary prayer in John’s Gospel:

“I ask not only on behalf of these but also on behalf of those who believe in me through their word, that they may all be one. As you, Father, are in me and I am in you, may they also be in us, so that the world may believe that you have sent me. The glory that you have given me I have given them, so that they may be one, as we are one, I in them and you in me, that they may become completely one, so that the world may know that you have sent me and have loved them even as you have loved me” (17:20-23).

This passage of John’s Gospel offers a timely vision of unity and interdependency: between Jesus and the Father, and between Jesus and his followers. This bi-directional movement between the divine and human identities is key to Ubuntu.

“The revelation of God through Jesus is one in which we are being invited into an identity,” Battle insisted. “And that identity is also inviting our identity. Interdependency is key to God’s self revelation, and our own relationships with one another.”

Shaped by this divine self-revelation, Ubuntu has repeatedly proven helpful in enabling people and groups to overcome seemingly intractable challenges. To illustrate this point, Rev. Battle introduced our group to an African Desert saying: The reason antelope walk together is so that one can blow the dust from the other’s eyes. Likewise, we need one another if we’re to see clearly.

African Desert Tradition: Tracing Ubuntu’s Historical Roots

While many are unaware of their life, work, and legacy, the African Desert Mothers and Fathers are responsible for the foundations of Christian spirituality and our prayer life. The reason this work is largely unknown even among many Christians to this day, Battle suggests, is because the early Jesus movement was “hijacked by the Graeco-Roman Empire,” and thus it “became associated with Western Civilization.” In this association, “Christianity became the Chaplaincy of Empires”—in a way that remains true in many ways and places today.

In response to Christianity’s changing relationship with the empire under Roman Emperor Constantine, Anthony of Egypt (c. 251–356) set out for the desert in resistance to the empire’s influence—founding the Desert Spirituality movement in the years to come. Though he came from a prominent family with access to wealth and status, Anthony gave up these privileges, which he believed were getting in the way of who God was calling him to be.

Pachomius of Egypt (c. 292–348) is another Desert Saint with whom most Christians are unfamiliar, though he is responsible for giving us the Monastic Rule of Life. While Anthony of Egypt was living in compelling ways that were drawing an increasing number of followers from the cities into the desert, Pachomius saw Anthony as something of a lone ranger.

Following a personal hero is destined to lead us astray, Pachomius believed. Christians ought to resist the cult of the individual, he taught, for Christian worship is essentially shaped by and for community.

“It’s not by accident that you’ve never heard of Pachomius,” Battle insists. “This African Saint really gives us the impetus for Ubuntu. We cannot even know ourselves [Pachomius taught], outside of being in community.”

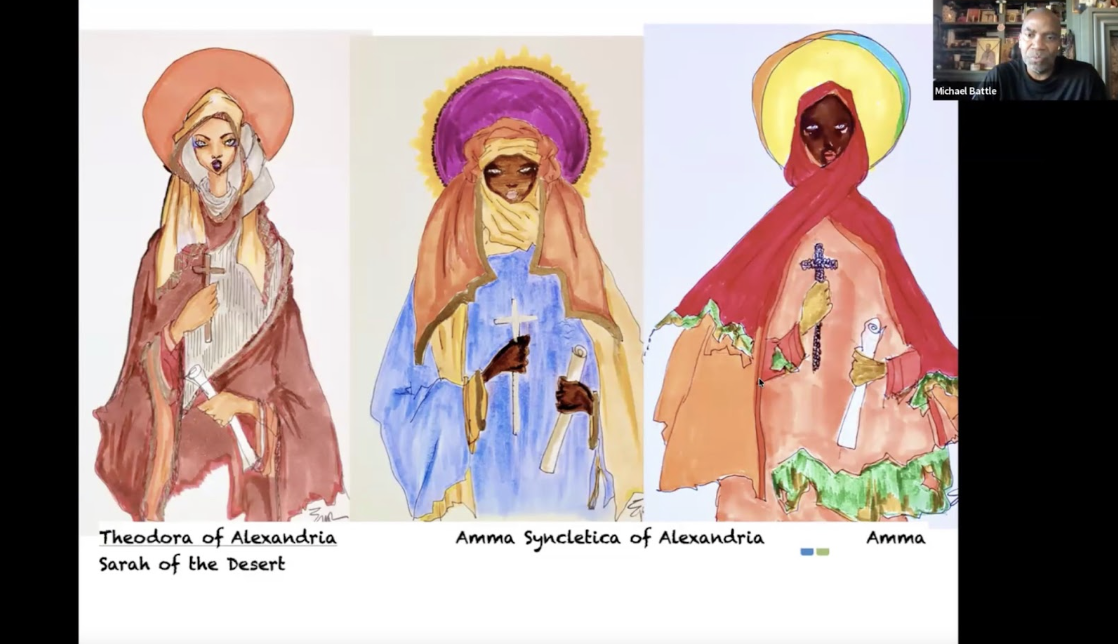

In addition to the Desert Fathers, Desert Mothers such as Theodora of Alexandria, Amma Syncletica of Alexandria, and Amma Sara of the Desert also helped to shape Christian spirituality in counter-cultural ways. These Desert Mothers played critical roles in ensuring that the most vulnerable didn’t fall through the social cracks: those who were widows, for example, those abandoned by parents, and those who were violently attacked by Graeco-Roman colonization efforts.

“These Desert Mothers were key to bringing human identity to those who did not otherwise share human identity in this empire,” Battle emphasizes. “Again, it’s not by accident that many of us do not know of their contributions.”

Ubuntu & Divine Revelation: Fundamental Interdependence

The work of the Desert Mothers and Fathers has direct threads to the development of Ubuntu, which refuses to deny full humanity to anyone. Ubuntu also refuses to locate human identity in the individual. Instead, Ubuntu says: “I am because you are.” And, “because you are, I am.”

In Western culture, shaped in large part by the teaching of seventeenth-century French philosopher Descartes and Enlightenment influence, our own sense of identity has been reduced to individual consciousness, summed up in the Latin axiom: Cogito, ergo sum—“I think therefore I am.”

“Placing sole authority in the perspective of the individual, that’s the position of Western European Enlightenment philosophy,” Battle pointed out, before drawing our attention to the corrective influence of Ubuntu and its divine roots.

“We need Ubuntu, not to represent co-dependency, as some have suggested. Ubuntu is inviting us into divine ways of being, not solipsistic, atomized, relativistic ways of being.”

“God’s self-revelation is relationality,” Battle reminded our group. Jesus insists that when his disciples see him, they see the Father (John 14:9). This claim that seeing Jesus is to see the Father reveals that relationships are essential to God’s nature. “The very substance of God is relationality,” Battle notes.

John’s Epistle puts the same point another way when he writes, “God is love” (1 John 4:8,16).” Because love requires an object, love assumes relationship. “Love is unintelligible until there is another to love.”

While such statements on love risk becoming platitudes, Battle invited our group to not miss the significance of this point: “On the most fundamental, almost quantum level, relationality is what makes us strong, makes us endure.” And, “this interdependency reminds us that God will never leave us alone.”

Learning from Desmond Tutu: Resisting Zero-Sum Violence & Individualism

Much of Rev. Battle’s writing and teaching has explored the teachings of South African Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu, whom Battle supported as a chaplain. Given Archbishop Tutu’s experience of prolonged injustice under apartheid in South Africa, one could easily imagine his trials turning him toward resentment, insisting on powering over or dominating his enemies after overcoming the grip of apartheid. Instead, he refused to respond in kind.

“Because he was such an advocate of God as Trinity, but also Ubuntu, Tutu couldn’t have an agonistic theology, or a zero-sum theology, because similar to King’s insight, ‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.’”

On January 30, 1956, the same day his parish home was bombed, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. addressed a standing-room only audience at First Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama: “We are a chain,” King preached. “We are linked together, and I cannot be what I ought to unless you are what you ought to be” (The Beloved Community, 36).

Appealing not merely to his own notions of peacemaking, strategies, or particular disposition, Dr. King appealed to his audience’s deepest understanding of the “overflowing love of God” (The Beloved Community, 37).

“There’s an interdependence that was obvious to people like King and Tutu,” Battle points out. “And not because such Christianity, as some would have us think, is only placating the White dominant identity. It’s not that folks like King or Tutu were weak. It’s a way of seeing that insists that ultimate answers have to be, and solutions must be, couched in interdependency.”

Turning the conversation over to Archbishop Desmond Tutu, we listened as Tutu reflected upon receiving the Templeton Prize: “The profound truth is, you cannot be human on your own. You are human through relationships. You become human… we were really made for human dependence.”

“I need you,” Archbishop Tutu insists. “In order to be me, I need you to be you to the fullest.”

Challenging the normative way of understanding identity in Western culture, Archbishop Tutu went on to say: “You are human not because you think. You are human because you participate in relationships. A person is a person through other persons. That is what we say. That is what the Bible says. And that is what our human experience teaches.”

Ubuntu & White Holiness Tradition

Rooted in the teaching of Desert Mothers and Fathers, Ubuntu grew into its current expression amidst the racist systems of apartheid in South Africa. Meaning “apartness,” apartheid refers to the formal, institutionalized system of separation and discrimination by whites against the majority Black population in South Africa from 1948 to 1994. As Battle notes, apartheid began in South Africa at the same time as Israel’s formation as a modern nation.

To be set apart has theological roots, as people, places, or even objects considered holy are often commanded to be set apart in scripture. As such, apartheid operated with a theological justification for treating some as inherently superior to others, according to race and ethnicity, while simultaneously justifying itself with a divine blessing.

Rather than understanding South African culture as dominant whites powering over and against Blacks, apartheid functioned in a more complex and nefarious manner. South African culture functioned with two white identities: Afrikaners and British. Afrikaners refers to a South African white ethnic group of Dutch descent. After facing discrimination by British settlers, Afrikaners took their frustrations out on indigenous Black populations in the form of racial aggression, discrimination, and eventual segregation. Apartheid became formalized and legally sanctioned under Afrikaner authority following the 1948 South African general elections.

Often in cases of trauma and affliction, there is a desire to look away from difficult realities, in an attempt to avoid seeing things as they are, Battle noted, reflecting on the experience of apartheid in South Africa. But, he insisted, there are other ways of responding to affliction. Entire swaths of people have been shaped by trauma and affliction in ways that have allowed them to see beyond their afflictions, into deeper realities, in ways that demand our full attention.

“The afflicted have no words to express what has happened to them,” French philosopher Simone Weil wrote. “Those who have never had contact with affliction…have no idea what it is.”

In contrast to the violence of apartheid’s systemic oppression, Ubuntu invites a way of seeing that allows us to see all others as full human beings, worthy of love, respect, and possessing inherent dignity.

Such a vision allows Ubuntu’s adherents to overcome otherwise intractable challenges, Rev. Battle insisted, by two commitments: persistently choosing to see the world differently, and taking part in small, intimate communities of practice, which together allow practitioners to better know themselves and others.

Ubuntu Circles & Experiencing True Freedom

As part of his work, Rev. Battle leads participants through Ubuntu Circles, where people practice an alternative way of being together. With agreed upon tones and intentional language, Ubuntu Circles encourage judgment without condemnation.

“We can form an opinion without turning to condemnation,” Rev. Battle points out. For example, using language such as “I notice…” or “I wonder…” invites wonder rather than subtle turns toward aggression and domination in the face of difference.

“Most victims of the European Enlightenment are prevented from truly getting to know one another—constantly trying to insert themselves as Alpha figures in interactions.”

Turning to an abridged version of David Foster Wallace’s well-known Kenyon College commencement address, “This is Water,” our cohort was reminded that seeing and inhabiting the world differently requires constant intentionality, resistance, and choices.

“Everything in my own immediate experience supports my deep belief that I am the absolute center of the universe,” Wallace notes. “It’s pretty much the same for all of us. It is our default setting, hard-wired into our boards at birth.”

“But there are other ways of thinking, if we choose,” Wallace offers—such as seeing myself not as the center of existence, but as a thread in a wider tapestry, and understanding that my wellbeing is inescapably bound to that of my neighbor.

Seeing others not as an imposition but as essential to my own flourishing requires repeated and persistent choices. It requires resisting voices that present my neighbors as my enemies, or represent them as a threat to my own safety, security, and well-being.

If we are to commit ourselves to mutual flourishing, to the fullness of life together we all long for most deeply, it has everything to do with cultivating awareness, and the intentional effort required to keep reminding ourselves: I cannot flourish without you.

If we choose to see the world differently and live in this way, Wallace says, “Even the most mundane experience can be seen as engulfed with meaning. That is real freedom!”

South Africa Today & Moving Forward Together

When asked how he would describe South Africa today, Rev. Michael Battle noted that we’re all human, and human behavior has a tendency to operate in cycles. This includes repeating past cycles of violence.

“But South Africa still has a distinct character to it,” he noted, “recognized the world over.”

“Now everyone can claim South African citizenship! That is huge. Other nation states will very likely be influenced by this way of life.”

In a concluding word, Rev. Battle offered the following recommendations to our Mosaic pastors cohort:

“We can start looking at each other differently now. There’s a lot of authority that’s been given to you, as a church leader.”

“Become more ecumenical, join other organizations. Continue to see other ways of being. And, be who you are—your true self.”

Further Reading:

- Ubuntu, by Michael Battle

- The Way of the Heart: The Spirituality of the Desert Fathers and Mothers, by Henri Nouwen

- Forgotten Desert Mothers, by Laura Swan

- The Beloved Community, by Charles Marsh

Photo: Red Charlie via Unsplash